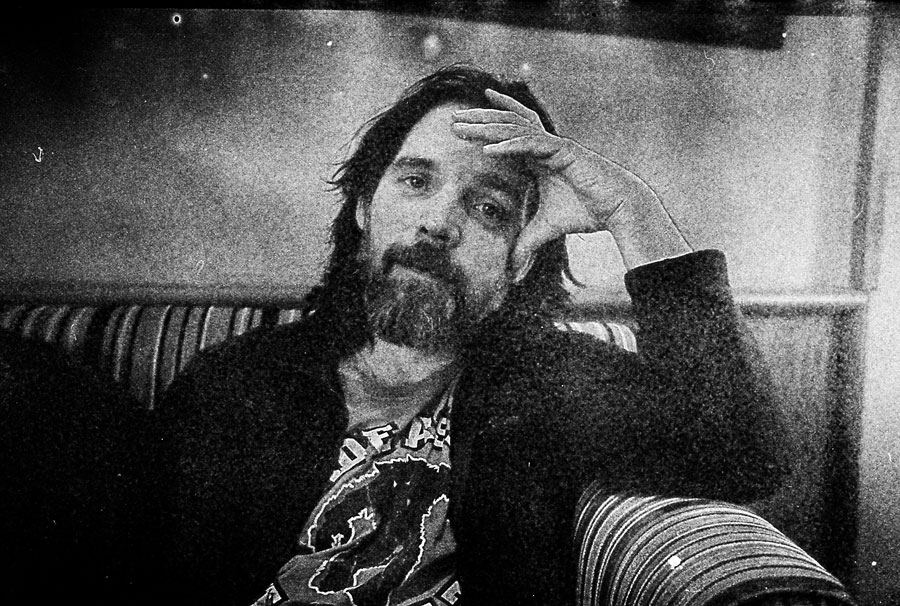

“Summertime”

“Summertime”

Superheadz Black Devil / expired Portra (thanks Marcello).

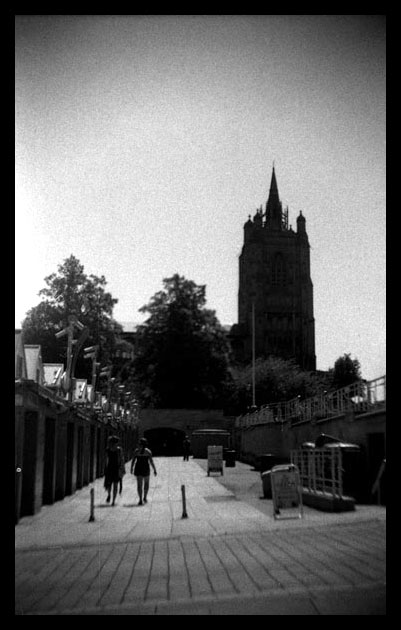

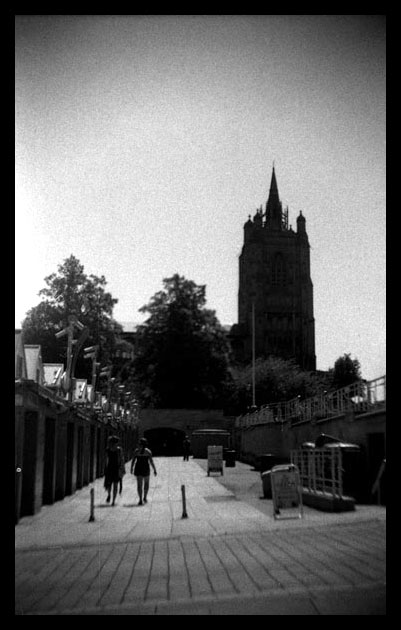

“Gaol Hill”

“Gaol Hill”

With the spire of St Mary’s overlooking Norwich Market.

Gakkenflex / Ilford HP5+

Once again, a steep learning curve

It wasn’t until I’d developed the film that I realised how much of the shot you lose to the top and bottom when shooting 35mm in a 127 medium format camera. So I’ve lost heads and feet… But, fortunately, most of the shots I took were either landscapes or far enough away not to be too significant.

This was a seriously fun experiment.

I’ll talk you through it.

I started off with a dark-bag, a canister of 36 exp Fujicolor C200 film, a 127 spool and used roll of backing paper, scissors, an empty plastic film canister, and a length of string with which to measure the amount of film I needed for the roll. I had already marked the backing paper with masking tape where the film needed to begin and where it would end and, in the dark-bag, I used that tape to fix it to the backing paper. I opened the canister, used the string to measure out the amount I needed, cut it off the rest of the roll and put the remainder into the black plastic film pot (which I marked with its contents). Then I fixed it, as mentioned, to the backing paper and wound it on to the spool. Which is all jolly good fun and gives a whole new lease of life to the expression ‘fumbling in the dark’.

Once it was wound really tight, I could use a little more masking tape to secure it, and then it was ready to load into the camera. A friend-in-the-know (that’s you, Juliet) mentioned that, since the 35mm is a more sensitive film, you need to cover the red window with some dark tape (I used electrical tape) and peel it back in subdued lighting in order to wind the film on to the next frame. This worked well.

Here are a couple of the shots (you can find the rest here and, for the sake of a laugh, if nothing else, I have included the headless shots  ):

):

Teddy running free

The Old Station House

Well, you live and learn.

Bencini Comet II S

I got ridiculously excited about this camera partly, I suspect, because it is *so* beautiful. Bright and shiny and small, with smooth motion and very simple mechanisms. But each time you use a new camera you are, of course, unaware of its capabilities or limitations.

This camera and film combination, I have discovered, is not much good for taking pictures of people. But photographs of architecture, under the right conditions, can be lovely. The lens on my copy is not very sharp, nor the focusing very accurate or easy, but I suspect that beautiful results could be achieved with a rich colour film and some woodland / countryside.

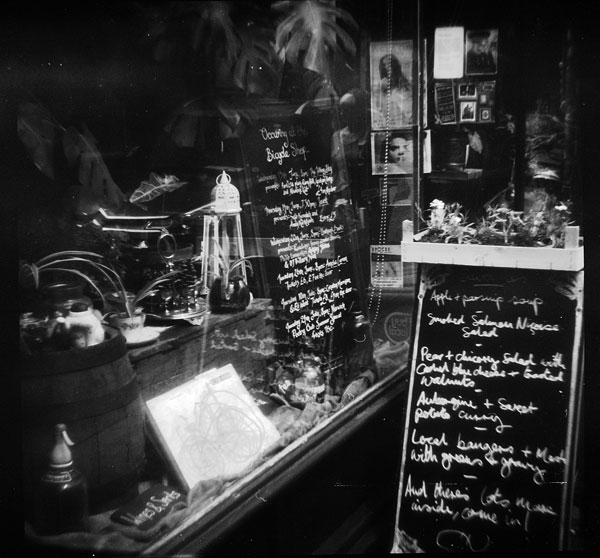

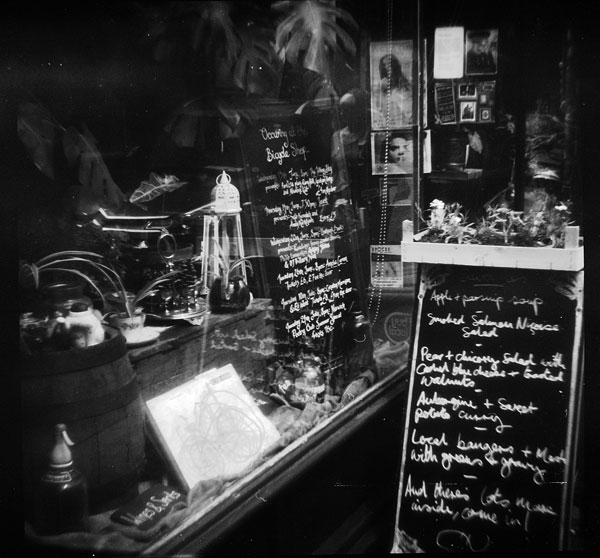

Out and about in Norwich yesterday, I saw this chalkboard and the one in the shop window and thought them rather charming. This, I believe, is one of the shots that came out best.

St Benedict's, Norwich

This one, too, I liked, of the Belgian Monk and the church next to it.

The Belgian Monk, Pottergate, Norwich

The rest of the roll can be found here.

I have just done something that felt rather brave and risky. In a dark bag, I spooled some 35mm film onto a 127 spool and backing paper, and I’ve loaded it into the Comet. Another experiment in the offing…

Camerapedia says of this camera:

“The Halina Paulette was a 35mm viewfinder camera made in Hong Kong by Haking. It was introduced in c.1965, with a 45mm/f2.8 lens in a 4-speed (1/30-1/250) + B shutter. “

Yesterday I developed a roll of Kodak TX400, the first I have put through this particular camera. And I developed it with some trepidation.

First off, the shutter makes such an unassuming noise, I was convinced it didn’t work. These two shots (which made me laugh out loud when I scanned them) are evidence that I was still looking through the lens to ascertain any aperture movement at all…

First off, the shutter makes such an unassuming noise, I was convinced it didn’t work. These two shots (which made me laugh out loud when I scanned them) are evidence that I was still looking through the lens to ascertain any aperture movement at all…

Then there was the problem of the camera-back, which seemed to me to be terribly loose. So I couldn’t be entirely sure the film hadn’t been completely light-flooded. My particular copy (which is rather a beautiful thing, I’m sure you’ll agree) has its own original case. So I decided to leave it in it, cumbersome as that might be, so as to minimise light-leaks. This worked to a degree, but as even these two shots show, it was very limited success, and some shots were too damaged to be viewable.

Then there was the problem of the camera-back, which seemed to me to be terribly loose. So I couldn’t be entirely sure the film hadn’t been completely light-flooded. My particular copy (which is rather a beautiful thing, I’m sure you’ll agree) has its own original case. So I decided to leave it in it, cumbersome as that might be, so as to minimise light-leaks. This worked to a degree, but as even these two shots show, it was very limited success, and some shots were too damaged to be viewable.

However, for me, shots such as this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or even this:

demonstrate its great potential.

demonstrate its great potential.

So here is a gallery of these and the remaining shots, and now I shall be attempting to fix that light-leak, loading her up with another roll of film, and having another go!

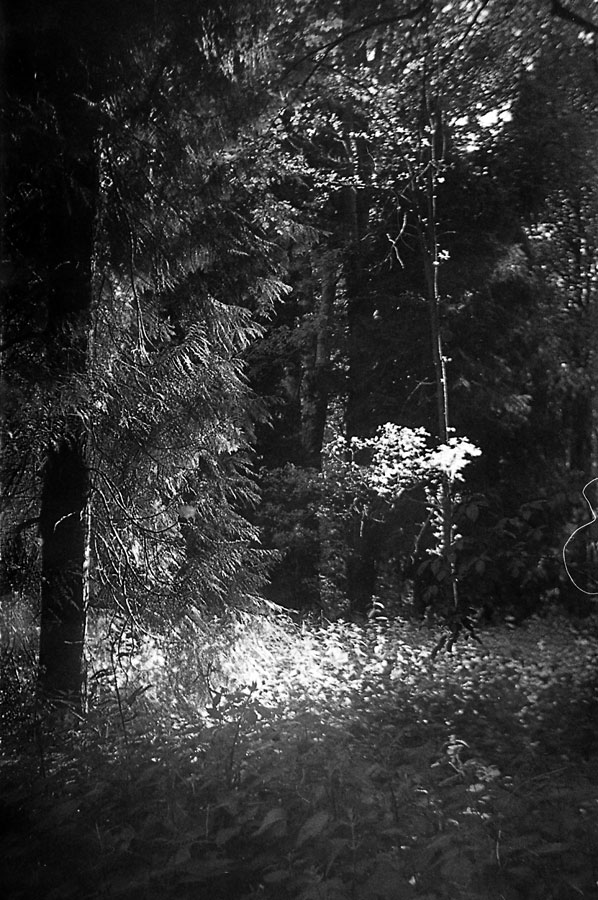

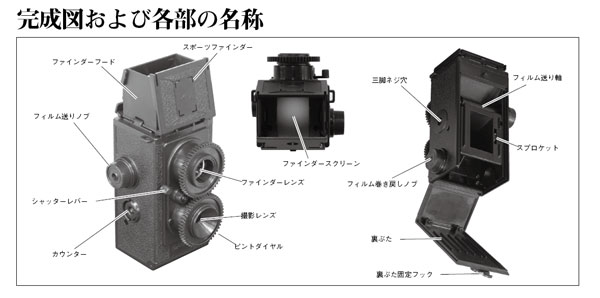

Gakkenflex / Ilford HP5 Plus

Taken yesterday.

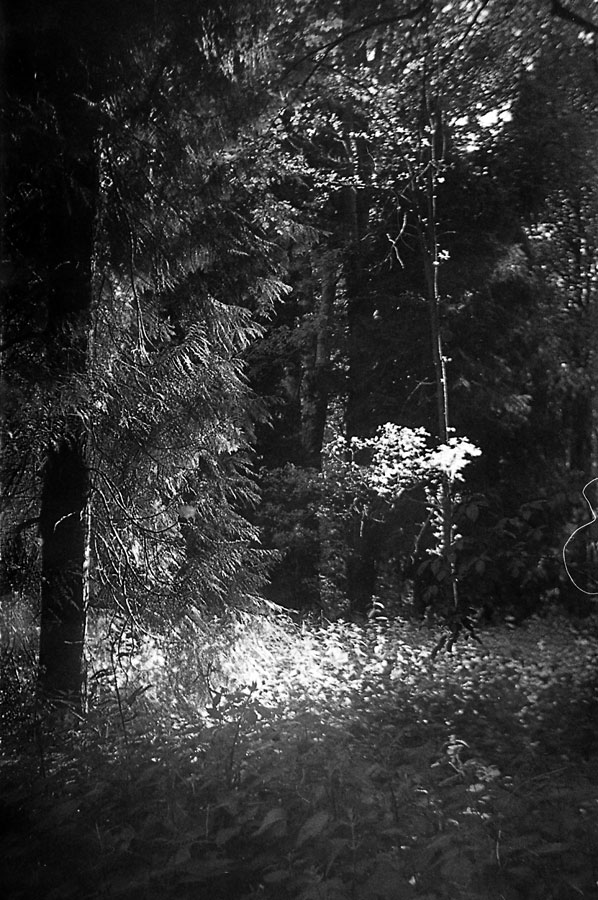

The more cameras I use, the greater my respect for lo-fi photography as a truly viable pursuit. Composition remains true regardless of the lens, and I love the Neptune end of the photographic polarity. That is of course photography’s natural state: chemical uncertainty. The rush to the wrong end of the polarity, toward Virgo and ever greater control, more megapixels, less chromatic aberration, instant verifiable results with the inconveniences cloned out after the fact in Photoshop is getting photography backward.

The more cameras I use, the greater my respect for lo-fi photography as a truly viable pursuit. Composition remains true regardless of the lens, and I love the Neptune end of the photographic polarity. That is of course photography’s natural state: chemical uncertainty. The rush to the wrong end of the polarity, toward Virgo and ever greater control, more megapixels, less chromatic aberration, instant verifiable results with the inconveniences cloned out after the fact in Photoshop is getting photography backward.

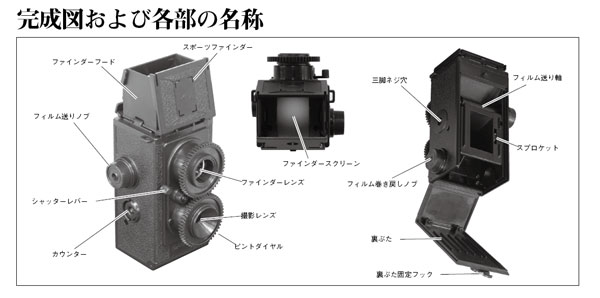

Recently I bought a Gakkenflex (pictured) which came originally from Japan. When first made this 35mm ‘Toy-TLR’ retailed for about 6 or 7 dollars, and was made entirely of plastic from a kit in a magazine. There are clones out there which give the same result for not much more. I also bought a Japanese Superheadz Black Devil and I took them both out today along with a 1956 Kodak Cresta II. There is simply no hope of controlling outcomes with any of these cameras, except in the most rudimentary terms. All you have is composition, and an understanding of which light will work, and which won’t.

And that is exactly what makes lo-fi photography so much fun, it has all the magical promise of uncertainty.

Yesterday I bought a new camera. It’s an Olympus 35 RC, a classic rangefinder made in 1970 and it cost me an incredible £36.75 on Ebay. I have been looking to buy an Olympus rangefinder ever since my 35 SP had to go back because its rangefinder was iffy (a fairly critical flaw in a rangefinder camera, since it is impossible to focus accurately). Rangefinder cameras are (for me at least) the perfect exposition of camera technology for a whole host of reasons, and the Olympus 35 RC is the perfect exposition of the rangefinder camera in my view. It is incredibly light and compact, you can focus almost instantly, and it takes great pictures. The 42mm Zuiko lenses on the Olympus rangefinders are a marvel. The SP has a 7 element lens, and the RC only 5 elements, but in a lens which is only 42mm across, it delivers amazing sharpness. The reason that elements matter in a lens is because they are required to project the subject uniformly, sharply and without aberration onto the film (or digital sensor). More elements delivers greater clarity and fewer aberrations, but before you even begin to project your image onto the film surface, the lens has to compensate for the design issues of the camera itself. A 42mm lens projects exactly onto 35mm film – since the diagonal measurement of a 35mm negative is 42mm. It is therefore the perfect focal length for a 35mm mechanism and it doesn’t need to distort the projected image at all to make it ‘fit’ the film. This means that all 5 elements are dedicated simply to providing clarity and sharpness. This is why 42mm rangefinders deliver such good quality images. The same principle plays out in medium format mechanics too, since most quality 120 rollfilm cameras ship with 80mm lens, as this is the diagonal measurement of medium format film.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

Nowadays, with your big DSLR cameras, the only way to compensate for the irregular distancing between the focal plane of your camera and the digital sensor (with a big mirror in between) is to have big lenses. This is the only reason that cameras and lenses have become so big. To deliver the equivalent quality of a 42mm rangefinder lens, a DSLR lens needs to be at least 4 or 5 times the size and weight.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

I am not going to get into digital bashing here, I firmly espouse the view that digital and film photography are not the same thing at all, and should not be compared, but it does seem to me that if I’d taken this picture with my phone camera, I wouldn’t be especially surprised, or even all that impressed.

It’s okay.

I think though that when you take chemicals out of the photography equation, then you are always going to get this predictable type of result. A digital photograph always looks like a digital photograph, whether your camera cost thirty-six or six thousand pounds.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t still take great photos, because the rules of composition will always find a synergy with unusual or arresting subject matter and create a great image, but somehow Leica has found a means to hypnotise people into forgetting this crucial fact. Which doesn’t mean that if I had money to burn I wouldn’t buy a 1955 M3 at the drop of a hat, but compared to the new Leica digitals, even that seems like a giveaway at somewhere around 700 quid.

ddd

My first cross-processed film. We bought some Fujicolor C200 from Eastern Europe, on eBay, and I processed the film in Ilford LC29 chemicals. This gallery contains some of the shots from that roll. I was pleasantly surprised by the results.