Yesterday I bought a new camera. It’s an Olympus 35 RC, a classic rangefinder made in 1970 and it cost me an incredible £36.75 on Ebay. I have been looking to buy an Olympus rangefinder ever since my 35 SP had to go back because its rangefinder was iffy (a fairly critical flaw in a rangefinder camera, since it is impossible to focus accurately). Rangefinder cameras are (for me at least) the perfect exposition of camera technology for a whole host of reasons, and the Olympus 35 RC is the perfect exposition of the rangefinder camera in my view. It is incredibly light and compact, you can focus almost instantly, and it takes great pictures. The 42mm Zuiko lenses on the Olympus rangefinders are a marvel. The SP has a 7 element lens, and the RC only 5 elements, but in a lens which is only 42mm across, it delivers amazing sharpness. The reason that elements matter in a lens is because they are required to project the subject uniformly, sharply and without aberration onto the film (or digital sensor). More elements delivers greater clarity and fewer aberrations, but before you even begin to project your image onto the film surface, the lens has to compensate for the design issues of the camera itself. A 42mm lens projects exactly onto 35mm film – since the diagonal measurement of a 35mm negative is 42mm. It is therefore the perfect focal length for a 35mm mechanism and it doesn’t need to distort the projected image at all to make it ‘fit’ the film. This means that all 5 elements are dedicated simply to providing clarity and sharpness. This is why 42mm rangefinders deliver such good quality images. The same principle plays out in medium format mechanics too, since most quality 120 rollfilm cameras ship with 80mm lens, as this is the diagonal measurement of medium format film.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

Nowadays, with your big DSLR cameras, the only way to compensate for the irregular distancing between the focal plane of your camera and the digital sensor (with a big mirror in between) is to have big lenses. This is the only reason that cameras and lenses have become so big. To deliver the equivalent quality of a 42mm rangefinder lens, a DSLR lens needs to be at least 4 or 5 times the size and weight.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

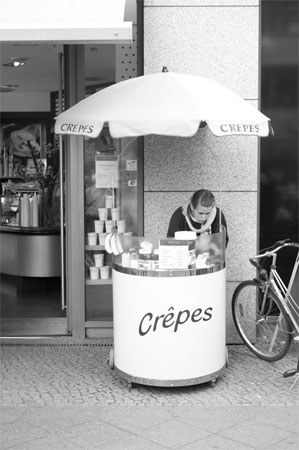

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

I am not going to get into digital bashing here, I firmly espouse the view that digital and film photography are not the same thing at all, and should not be compared, but it does seem to me that if I’d taken this picture with my phone camera, I wouldn’t be especially surprised, or even all that impressed.

It’s okay.

I think though that when you take chemicals out of the photography equation, then you are always going to get this predictable type of result. A digital photograph always looks like a digital photograph, whether your camera cost thirty-six or six thousand pounds.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t still take great photos, because the rules of composition will always find a synergy with unusual or arresting subject matter and create a great image, but somehow Leica has found a means to hypnotise people into forgetting this crucial fact. Which doesn’t mean that if I had money to burn I wouldn’t buy a 1955 M3 at the drop of a hat, but compared to the new Leica digitals, even that seems like a giveaway at somewhere around 700 quid.