Blog Archives: Articles

Lo-Fi

The more cameras I use, the greater my respect for lo-fi photography as a truly viable pursuit. Composition remains true regardless of the lens, and I love the Neptune end of the photographic polarity. That is of course photography’s natural state: chemical uncertainty. The rush to the wrong end of the polarity, toward Virgo and ever greater control, more megapixels, less chromatic aberration, instant verifiable results with the inconveniences cloned out after the fact in Photoshop is getting photography backward.

The more cameras I use, the greater my respect for lo-fi photography as a truly viable pursuit. Composition remains true regardless of the lens, and I love the Neptune end of the photographic polarity. That is of course photography’s natural state: chemical uncertainty. The rush to the wrong end of the polarity, toward Virgo and ever greater control, more megapixels, less chromatic aberration, instant verifiable results with the inconveniences cloned out after the fact in Photoshop is getting photography backward.

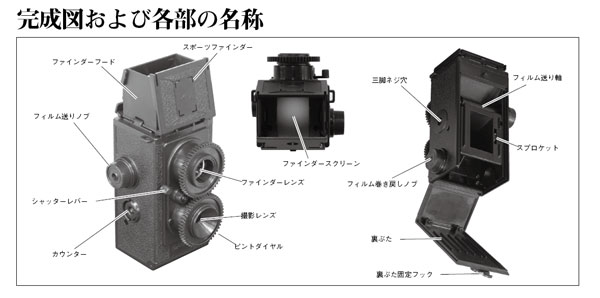

Recently I bought a Gakkenflex (pictured) which came originally from Japan. When first made this 35mm ‘Toy-TLR’ retailed for about 6 or 7 dollars, and was made entirely of plastic from a kit in a magazine. There are clones out there which give the same result for not much more. I also bought a Japanese Superheadz Black Devil and I took them both out today along with a 1956 Kodak Cresta II. There is simply no hope of controlling outcomes with any of these cameras, except in the most rudimentary terms. All you have is composition, and an understanding of which light will work, and which won’t.

And that is exactly what makes lo-fi photography so much fun, it has all the magical promise of uncertainty.

Ensign Ful-Vue

Last week, whilst trawling our local antique (and junk) shops, Jem came across this funky little camera, which he promptly bought for a fiver (“Well… it would have been rude not to!”) and which I promptly fell in love with. My instant love-affair with it meant he gifted it straight to me.

Last week, whilst trawling our local antique (and junk) shops, Jem came across this funky little camera, which he promptly bought for a fiver (“Well… it would have been rude not to!”) and which I promptly fell in love with. My instant love-affair with it meant he gifted it straight to me. ![]()

Yesterday I loaded it up with expired Ilford XP2 film, which is our usual M.O. if we aren’t yet sure if a camera works properly or not, and off we went to try out our very old cameras: Jem was using his Box Brownie for the first time.

This little gem was made between 1946 and 1949. It is a TLR with a beautiful big Brilliant-style reflex viewfinder on the top. It is a unique thing – pretty avant-garde for its time – as it was the first ‘streamlined’ box-style camera of its type. It has a fixed shutter of 1/30th of a second and a fixed aperture of f11. Rather charmingly, if you pull the tiny lens out a little way, you can take close-ups of 3-9 feet, and push it back in for 9 feet or more.

My first hurdle, upon taking it out of my bag for the first shot, was discovering that the mirror has come loose and was rattling around inside the viewfinder compartment. Nothing I can do about that until I’ve finished the roll, so for now I have to give it a gentle shake to reposition it and take my shots *very* carefully…. Of course I can’t be entirely sure it’s back in perfect position either, so there may be some funny angles resulting from this experiment!

I’m halfway through the roll, and hope to have it finished, developed and the results posted up here some time next week.

Leica Madness

Yesterday I bought a new camera. It’s an Olympus 35 RC, a classic rangefinder made in 1970 and it cost me an incredible £36.75 on Ebay. I have been looking to buy an Olympus rangefinder ever since my 35 SP had to go back because its rangefinder was iffy (a fairly critical flaw in a rangefinder camera, since it is impossible to focus accurately). Rangefinder cameras are (for me at least) the perfect exposition of camera technology for a whole host of reasons, and the Olympus 35 RC is the perfect exposition of the rangefinder camera in my view. It is incredibly light and compact, you can focus almost instantly, and it takes great pictures. The 42mm Zuiko lenses on the Olympus rangefinders are a marvel. The SP has a 7 element lens, and the RC only 5 elements, but in a lens which is only 42mm across, it delivers amazing sharpness. The reason that elements matter in a lens is because they are required to project the subject uniformly, sharply and without aberration onto the film (or digital sensor). More elements delivers greater clarity and fewer aberrations, but before you even begin to project your image onto the film surface, the lens has to compensate for the design issues of the camera itself. A 42mm lens projects exactly onto 35mm film – since the diagonal measurement of a 35mm negative is 42mm. It is therefore the perfect focal length for a 35mm mechanism and it doesn’t need to distort the projected image at all to make it ‘fit’ the film. This means that all 5 elements are dedicated simply to providing clarity and sharpness. This is why 42mm rangefinders deliver such good quality images. The same principle plays out in medium format mechanics too, since most quality 120 rollfilm cameras ship with 80mm lens, as this is the diagonal measurement of medium format film.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

The first rangefinder ever made for production was the Leica 0. It was a prototype made in 1923 by Oskar Barnack and he used a Leitz Summar lens to fit on his prototype body. The reason he used a 50mm lens, rather than a natural fit 42mm lens, was because the company weren’t prepared to manufacture a new lens for an experimental camera design. It is for this reason, and this reason alone that rangefinder cameras have traditionally shipped with a 50mm lens, because the first Leica prototype had a 50mm lens, so all subsequent rangefinders, which were for the first few decades simply Leica copies, had 50mm lenses. From day one therefore the 5 element Zeiss lenses had to account for the 8mm of distortion, which is no big deal because the Zeiss lenses were of sufficiently high quality to cope, but a 42mm lens could have been even smaller and sharper because it would not have needed to compensate for the film back.

Nowadays, with your big DSLR cameras, the only way to compensate for the irregular distancing between the focal plane of your camera and the digital sensor (with a big mirror in between) is to have big lenses. This is the only reason that cameras and lenses have become so big. To deliver the equivalent quality of a 42mm rangefinder lens, a DSLR lens needs to be at least 4 or 5 times the size and weight.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

The Leica 0 is a rare camera and only 12 are known to exist. One sold a couple of days back for a staggering $2.8 million in Vienna. Leica cameras have a powerful brand and identity, which is why they cost so much money and they have done a miracle marketing job to be able to charge the prices they do for digital equipment. Even so, the rangefinder philosophy holds to this day. By taking the mirror out of the SLR and fitting a rangefinder instead, the lens can really deliver. A few days back Leica announced the release of a new black and white only digital rangefinder, the Leica Monochrom, and even if it is a Leica, even if it has a truly incredible lens, and even if it is a beautifully engineered rangefinder, it still should not cost $8000, that is £6225.

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

If you translate that into film costs, and home processing, and spend your money on an Olympus 35RC, then I estimate that it will keep you in photographs for about 50 years. But of course, it’s not about cost, it’s about results, right? Here then (left) is an image taken with the new Leica.

I am not going to get into digital bashing here, I firmly espouse the view that digital and film photography are not the same thing at all, and should not be compared, but it does seem to me that if I’d taken this picture with my phone camera, I wouldn’t be especially surprised, or even all that impressed.

It’s okay.

I think though that when you take chemicals out of the photography equation, then you are always going to get this predictable type of result. A digital photograph always looks like a digital photograph, whether your camera cost thirty-six or six thousand pounds.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t still take great photos, because the rules of composition will always find a synergy with unusual or arresting subject matter and create a great image, but somehow Leica has found a means to hypnotise people into forgetting this crucial fact. Which doesn’t mean that if I had money to burn I wouldn’t buy a 1955 M3 at the drop of a hat, but compared to the new Leica digitals, even that seems like a giveaway at somewhere around 700 quid.

Zeiss Ikon Nettar

Today I have listed the Zeiss Ikon Nettar folder on Ebay. I have got to the stage where I cannot reasonably buy any more cameras without losing a few and since we have three other folders in the house, all of which have more appealing attributes than this, the Zeiss is leaving. There’s Alice’s Ensign Ranger, which is of somewhat better quality, and my Voigtlander Bessa, which is of much higher quality, and then there is Alice’s Kodak Vest Pocket, which dates from the first world war. You can see why the Nettar was chosen as the sacrifice.

Today I have listed the Zeiss Ikon Nettar folder on Ebay. I have got to the stage where I cannot reasonably buy any more cameras without losing a few and since we have three other folders in the house, all of which have more appealing attributes than this, the Zeiss is leaving. There’s Alice’s Ensign Ranger, which is of somewhat better quality, and my Voigtlander Bessa, which is of much higher quality, and then there is Alice’s Kodak Vest Pocket, which dates from the first world war. You can see why the Nettar was chosen as the sacrifice.

It is always painful to part with a camera, even if you believe that you’re unlikely to use it again, and this particular camera got some pleasing results, despite its very old, and incredibly slow, lens. It is still beautifully made and if you are patient with it, this folder is capable of getting good results. This photo of the beautiful cloisters at Norwich Cathedral was taken with it.

I am also fixing up another Voigtlander, this a ‘Brilliant’ TLR, which was the template from which the Lubitel was forged. In fact, the Lubitel 2 is a near identical copy of the Brilliant, but made with an intriguing hotch-potch of cheaper materials and more current technologies. The mirror had lost most of its silvering and some of the screws holding the waist-level finder in place were rusted through. I gave the camera a thorough clean and service yesterday and today I bought a glass cutter and a cheap make-up mirror and I’ll cut a new lens mirror for it and that should make it as good as new, which is no mean feat for a camera that is 80 years old.

Norfolk Broads

We spent yesterday on a ‘field trip’ in the nearby environs of Rockland Saint Mary – in the heart of the Norfolk Broads. It’s a really beautiful part of the country, I went on a holiday there for a week with some friends when I was younger and we had a fantastic time fishing for eels and frying them up for breakfast on the boat stove. It was a rather wild and unkempt place back then.

Going back there yesterday, I was initially taken aback by how much it had changed. It seemed that every hedge was neatly trimmed, all the grass verges were mowed to a regulation length, and all the paths were properly edged and signposted. All trace of the splendid wilderness of 20 years ago seemed to have vanished.

Maybe this is just a reflection of our times, it seems to me that there is no delapidation, ruin or decay allowed in the world anymore and everyone works very hard to turn our great wildernesses into golf courses. Why would that be? The world is losing its character in this way, and one place looks much the same as any other. The English countryside is becoming uniformly twee.

Even so, there were some beautiful sights and sweeping vistas. I went out with the two mamiyas – the 645 and the 330 – and hopefully there will be some pleasing results after our long day’s walking. I must add that the photography seemed to flow better after our halfway stop at a riverside pub. Neptune loves company!

Kodak Duex

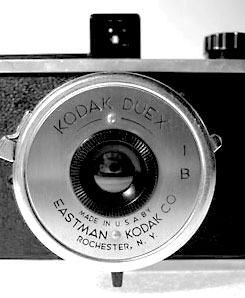

Yesterday I spotted an old boxed camera on the top shelf of my study. Okay, it’s not so much a study, as a space under the stairs which nobody else is interested in, but there are shelves there and a desk, so it’s a kind of study. The camera is a Kodak Duex, which is just one consonant short of unfortunate. It is a very funny camera, made in 1940, takes 620 film and has no options at all! This is even more point and click than the camera on my phone, which needs to be fired up before I can use it.

Yesterday I spotted an old boxed camera on the top shelf of my study. Okay, it’s not so much a study, as a space under the stairs which nobody else is interested in, but there are shelves there and a desk, so it’s a kind of study. The camera is a Kodak Duex, which is just one consonant short of unfortunate. It is a very funny camera, made in 1940, takes 620 film and has no options at all! This is even more point and click than the camera on my phone, which needs to be fired up before I can use it.

The body is Bakelite and the lens spirals out from the camera body, giving the correct focusing distance from the lens to the film surface. The shutter fires at a very shake-inducing 1/30th of a second, so I am not sure it will be easy to use at all. Anyhow, I’d left this camera in its box for a few months without realising that I had already put some film in it! I have a lot of work to do today, but when I’ve got through some of that I shall go out for a walk and see how it goes.

Time Travel

Today I finished posting all the galleries I’m going to be putting up here. I count 13 altogether, which means that I’ve processed film from 13 different cameras, which are listed in a vague chronological order of manufacture, from the Zeiss Ikon Nettar (the 517/16) made in 1949, to the Canon EOS 5, manufactured in the mid 1990′s. I have used older cameras – like for example the Voigtlander Bessa of 1937 which requires a light-leak fix before I can safely publish any photos – and eventually I hope to get a turn of the (20th) century plate camera to really get a feel for the beginnings of photography.

I am also getting to the stage where I’m beginning to settle on a couple of cameras for various applications. I really enjoyed using the Olympus 35 SP for a walkabout camera, even though my copy was cranky as hell and didn’t have a functioning spot-meter. I love the Zorki for the same reasons, so although I still believe the Canon A-1 is the perfect all-rounder I’m not sure I am going to be taking too many more shots with it, for a while at least. I do have a roll of infrared I want to put through it, but other than that I think I will get a decent rangefinder for general use. I might go with the Olympus, or perhaps a Nikon S2 or some other similar Leica style.

I also appreciate the style of the Halina 35x and too the Ilford Sprite so I’m very happy to continue using old, odd cameras whenever I can find one. The Hunter-Gilbert was a real surprise and it only cost me £3 on Ebay. For the future I have film loaded into a Kodak Instamatic (from 1976) and an Argus C3 Rangefinder, the camera which popularised photography in the USA. There’s nothing like moving through the history of photography in this way, you really begin to understand how the art and science of cameras evolved over time. When you pick up a rangefinder you really appreciate the technology that allows you to focus the camera without moving yourself or your subject to fit the readings on the lens barrel. And as for exposure meters!

There is something quite magical though about a camera which only has one or two shutter settings and no means of focusing except a very narrow aperture! You have to work with the camera, understand it and what it needs and then it makes no difference how out of date the thing is, it will still take a beautiful picture.

Cross-Processed Fujicolor C200

My first cross-processed film.

We bought some Fujicolor C200 from Bulgaria, on eBay, and I processed the film in Ilford LC29 (black and white) chemicals. This gallery contains some of the shots from that roll. I was pleasantly surprised by the results. ![]()

A not-quite-dead film

Just had a totally magical experience.

Yesterday, I developed a film with some trepidation. I had brought it with me, in my camera, before Jem and I were together.

I wasn’t sure what would be on it.

As

it was, the Universe fixed that problem for me. As I spooled it in the

dark bag, it was horribly stuck together and my heart began to sink.

As I went through the developing process, more bits of film disintegrated away with each chemical emptied out of the tank.

I

took it out of the tank and there was nothing left. Just scraps of what

once was film on the long plastic reel. I hung it out to dry thinking

at the very least we could use the film to teach the boys how to wind it

onto a spool.

Then, today, just before either ditching it or putting it away, I looked closer and saw a little face.

Only two partial prints had survived. Both of a baby Bert (of whom I now own precious few photographs).

And here he is…