Tag Archives: Norfolk

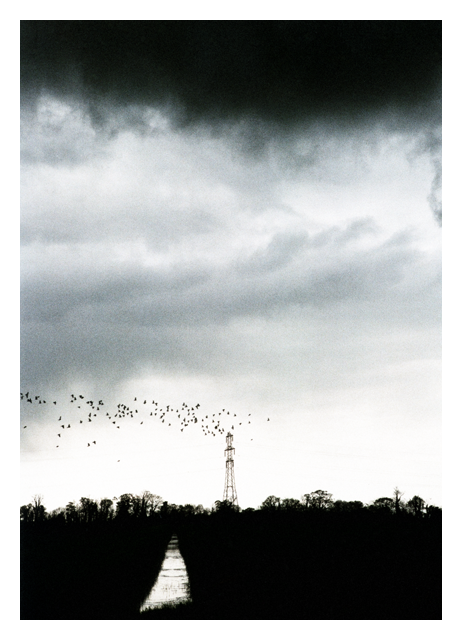

Winter Birds

“Winter Birds”

Zorki 4 / Fuji film

A classic Norfolk skyline, far out in the fens. In this house we have discovered a love of Rilke, and this brings him to mind:

“Therefore, dear Sir, love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you. For those who are near you are far away… and this shows that the space around you is beginning to grow vast…. be happy about your growth, in which of course you can’t take anyone with you, and be gentle with those who stay behind; be confident and calm in front of them and don’t torment them with your doubts and don’t frighten them with your faith or joy, which they wouldn’t be able to comprehend. Seek out some simple and true feeling of what you have in common with them, which doesn’t necessarily have to alter when you yourself change again and again; when you see them, love life in a form that is not your own and be indulgent toward those who are growing old, who are afraid of the aloneness that you trust…. and don’t expect any understanding; but believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance, and have faith that in this love there is a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it.”

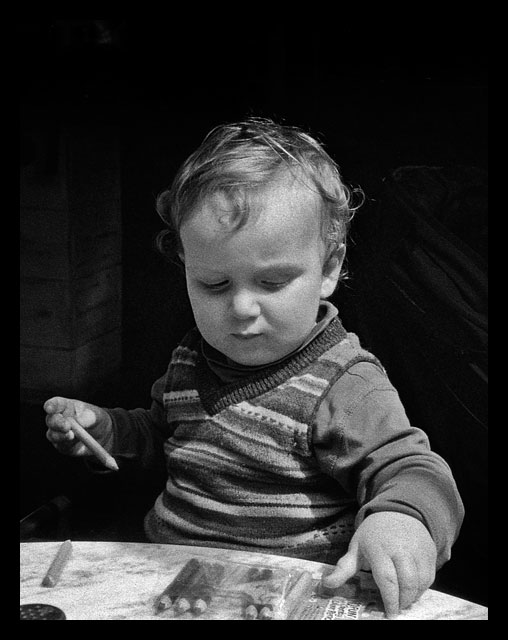

Drawing Time

“Drawing Time”

Olympus 35RC / Ilford HP5+

Here is Ted, looking very smart in the tank top that his grandma knitted for him.

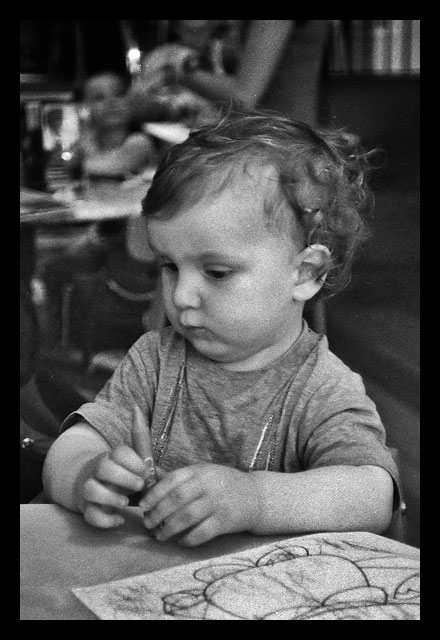

Reverie

“Reverie”

Olympus 35RC / Ilford HP5+

Our Internet has stopped working this week: indeed, it will be next week before the phone company can fix it, and that, as you might imagine, for somebody whose work is dependent on having web access, is nothing short of a nightmare. We have some access via a wireless hotspot in the village, but it is slow and inconsistent. I am trying to get some film finished up. I am out today with a Kodak Colorsnap 35 (incongruously loaded with black and white) and when I get that used up I shall move onto the Halina. When I’m done with that (before Christmas) I shall load up my Canon IIB, which I bought from Moscow a while back. It is an unbelievably beautiful camera and in almost new condition. I am really looking forward to using it over Christmas.

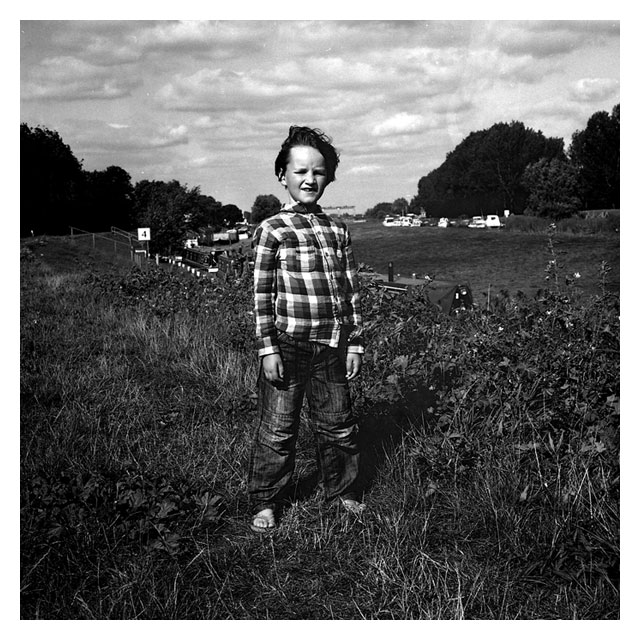

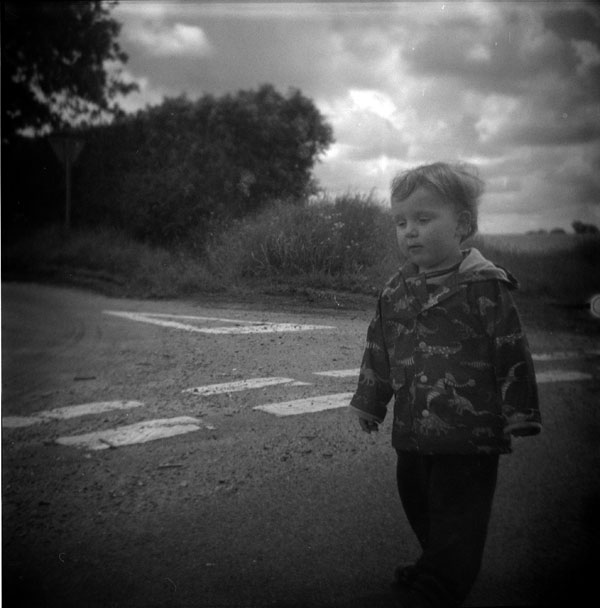

Ted

“Ted”

Olympus 35RC / Ilford HP5+

I mentioned this scenario just the other day on here, this is a fairly old photo now, taken on an Olympus rangefinder which I’ve had film in for several months. Some of the frames have deteriorated (but they are even so, entirely valid) and some bring a smile because they are forgotten times. This is one such, with Ted looking a little sceptical. He is probably wondering where his breakfast might be.

The Anchor Brewery

Viewed from St. Benedict’s in Norwich

Kodak Duex / Fuji Pro

This shot was mostly an experiment taken with the 1940 Kodak Duex, I was keen to see what it would do with some high-saturation colour film in it. I have discovered that it only really likes somewhat distant subjects (over 8 feet) and good light.

Bullards ceased beer production in 1966 and the impressive edifice is now home to an insurance company. Now that’s dissonance!

1938 Voigtländer Brilliant

There has been quite a saga accompanying this camera. The Voigtländer Brilliant of 1938 was the world’s first focusing TLR, and as a template it has spawned several copies, most notably the Lomo produced Lubitels (of which we have two), but even if the copies are great – for reasons of lomography – they don’t quite have the pedigree of the Voigtländer. I realised after trustingly putting a roll of Ilford through it that the focusing mechanism was off kilter, so I resolved to try it again using zone focus and a roll of Ektar.

There has been quite a saga accompanying this camera. The Voigtländer Brilliant of 1938 was the world’s first focusing TLR, and as a template it has spawned several copies, most notably the Lomo produced Lubitels (of which we have two), but even if the copies are great – for reasons of lomography – they don’t quite have the pedigree of the Voigtländer. I realised after trustingly putting a roll of Ilford through it that the focusing mechanism was off kilter, so I resolved to try it again using zone focus and a roll of Ektar.

It has taken a while to get the camera this far. I bought it very cheaply last year and like all of the Brilliants, it hadn’t aged especially well. The finder was loose and rusted, the mirror had lost nearly all its silver, the film chamber’s painted interior was flaky and the counter wouldn’t move. I cut a new mirror and replaced it then set to work drilling out the rusted screws from the finder. I carefully removed the prism finder and put it out of the way: it’s a beautiful and precise piece of glasswork after all, then a few moments later heard a crash. I looked up to see that one of the boys had decided to have a look at this rather gleaming jewel, picked it up and promptly dropped it on the floor.

Even though I immediately recognised this as an excellent opportunity to practise mindfulness, I was still devastated. The entire corner of the prism was smashed and at first glance it looked as though the camera was going to have to go for spares.

In the end I cleaned it all up and put it back together anyway and found that because the finder hood covered a good portion of the prism, it was still in fact usable. I wasn’t able to fix the focus because the viewing lens was moving freely through its range in tandem with the taking lens, there was nothing to adjust. For some reason, it just doesn’t match up anymore. I suspected that this might be because the infinity stop had shifted but I checked the film plane for accuracy and it seemed good. So I loaded up some Ektar and took it to Norwich with me at the weekend.

The reason that focusing Brilliants with good glass are so desirable is not so much the focusing ability of the camera, but the quality of the Skopar lens. It operates at a very decent ƒ3.5, and is reputed to have excellent characteristics. The vast majority of surviving Brilliants have much less capable lenses than the Skopar.

Upon seeing a few of the results, I have to agree. This camera takes a great deal of patience to use, it is after all 74 years old now, and has taken a few knocks, both old and new, but it is still a classy performer all the same, as you can see.

Even so, I think I shall be selling it. Even without a focusing viewing lens, a partly smashed prism and a non-functional film counter I think I can get a decent price for it because the lens is gold, and as any serious photographer will tell you, the lens is pretty much the whole story, regardless of its innate style. I love plastic lenses, which cost a few pence, but they give a very different style. If you are looking for accuracy, then the Skopar beats many more modern competitors hands-down.

Plus, I recently bought a Yashica from Pakistan and I cannot really justify owning five TLRs!

Ensign Ful-Vue Super in Monochrome

After the roaring success of the Ful-Vue Super in colour (Ektar, to be precise), I decided to give it a go in black and white. So I filed down a roll of Ilford HP5 120 film to fit (it being a 620 medium format camera), loaded it up and off I went. (Home-developed in Ilford LC29 and home-scanned).

The results can be found here. But here are one or two to be going on with:

The only problem I had is that once again it began sticking and slipping at around exposure 4, and by number 10 I had to give up winding on, so I have lost 2 shots per roll so far. And on a roll of film that only contains 12 exposures anyway, that’s a pricey fault!

I suspect that the culprit is the filed down 120 film. 120 comes on a much thicker spool and I don’t think the more streamlined mechanism is coping with it at all well, so for the next roll, I’m going to have to attempt respooling 120 film onto a 620 spool. I am assured that once you’ve got the hang of it there’s really nothing to it…

*gulp*

![]()

Wish me luck!

Bencini Comet IIS loaded with 35mm Fujicolor C200

Once again, a steep learning curve ![]()

It wasn’t until I’d developed the film that I realised how much of the shot you lose to the top and bottom when shooting 35mm in a 127 medium format camera. So I’ve lost heads and feet… But, fortunately, most of the shots I took were either landscapes or far enough away not to be too significant.

This was a seriously fun experiment.

I’ll talk you through it.

I started off with a dark-bag, a canister of 36 exp Fujicolor C200 film, a 127 spool and used roll of backing paper, scissors, an empty plastic film canister, and a length of string with which to measure the amount of film I needed for the roll. I had already marked the backing paper with masking tape where the film needed to begin and where it would end and, in the dark-bag, I used that tape to fix it to the backing paper. I opened the canister, used the string to measure out the amount I needed, cut it off the rest of the roll and put the remainder into the black plastic film pot (which I marked with its contents). Then I fixed it, as mentioned, to the backing paper and wound it on to the spool. Which is all jolly good fun and gives a whole new lease of life to the expression ‘fumbling in the dark’.

Once it was wound really tight, I could use a little more masking tape to secure it, and then it was ready to load into the camera. A friend-in-the-know (that’s you, Juliet) mentioned that, since the 35mm is a more sensitive film, you need to cover the red window with some dark tape (I used electrical tape) and peel it back in subdued lighting in order to wind the film on to the next frame. This worked well.

Here are a couple of the shots (you can find the rest here and, for the sake of a laugh, if nothing else, I have included the headless shots ![]() ):

):